Why blockchain data architecture matters for researchers

When you move from reading whitepapers to doing actual empirical work on Ethereum, Bitcoin, Solana or any other network, the first hard wall you hit is data. Raw blocks and transactions are technically “public”, but without a clear blockchain data architecture you end up drowning in JSON, RPC calls and half-broken scripts. For researchers, the difference between a one-off exploratory script and a robust analytical pipeline is precisely in how you design storage, indexing, provenance and reproducibility from day zero. Treat the chain not as an API you poke occasionally, but as a complex, append-only distributed database that requires intentional modeling, just like any relational warehouse or graph store in a traditional data engineering stack.

Step 1: Clarify your research questions and data granularity

From vague idea to explicit data requirements

Before choosing a node provider, a blockchain data analytics platform or writing a single line of code, reduce your research question to hard constraints on data. For example, “measure MEV extraction in DeFi” implicitly defines block-level, transaction-level and sometimes event-level granularity. Ask yourself: do I need every trace of internal calls, or only high-level transfers? Do I require full historical data or just a rolling window? Will I compare multiple chains or focus on one network? Being explicit here dictates the cardinality of your tables, your indexing strategy and the feasibility of your study, and it also prevents you from quietly switching definitions halfway through the project, which is a subtle but common source of irreproducible results and misleading empirical findings.

Common mistakes at the problem-definition stage

Researchers often jump directly into RPC endpoints, copy-paste some community script, and only later notice that key variables are missing or defined inconsistently. A classic error is underestimating the complexity of logs and events: you think you only need “swaps”, but each DEX encodes them differently, and contract upgrades change event formats over time. Another frequent trap is to conflate “account balance” with “state”, ignoring historical deltas. This makes it impossible to reconstruct past positions or verify prior states. To avoid this, treat every core concept—user, contract, position, trade, validator—as an entity in an explicit data model instead of as a loosely defined object you patch during analysis.

Step 2: Decide how you will access blockchain data

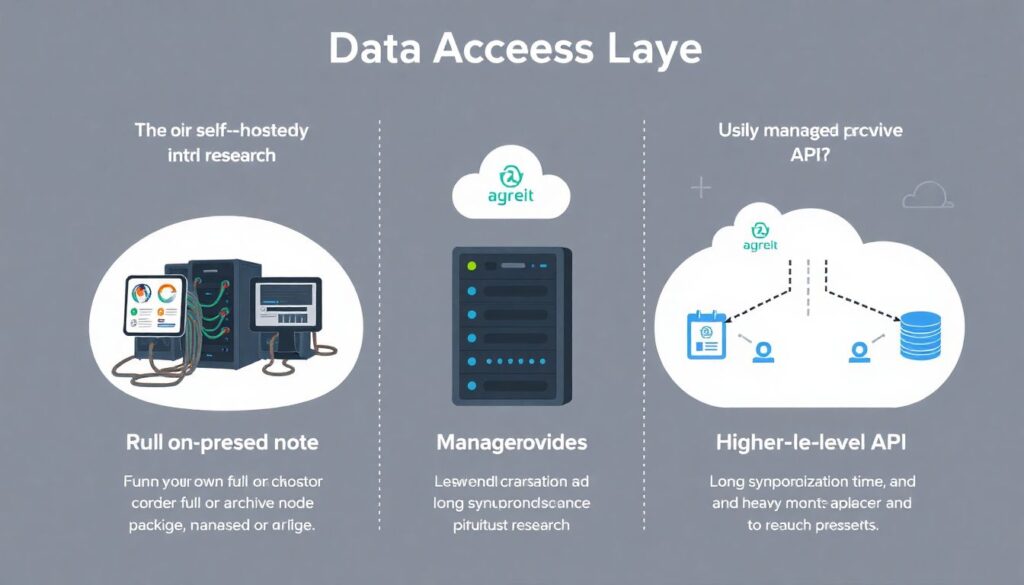

Node strategies: full, archive, or third-party providers

At the data access layer, you choose between running your own node, relying on managed providers, or using higher-level APIs. Running a full or archive node grants maximum control and auditability, which is attractive for rigorous research, but the operational cost, synchronization time and maintenance are non-trivial. Managed RPC providers offer convenient endpoints but often rate-limit historical or trace-heavy queries, which can distort sampling if you are not vigilant. For exploratory work, mixing both can work: use a provider for rapid prototyping, then re-run the final extraction against your own reproducible infrastructure when moving to publication-grade datasets.

Higher-level APIs and unconventional access patterns

Instead of manually crawling blocks, consider composable APIs that expose decoded events, internal traces and standardized schemas. Some services effectively operate as a blockchain data analytics platform built on top of raw nodes, offering pre-parsed transfer tables, contract metadata and labeling. An unconventional but powerful tactic is to split your pipeline into two modes: “fast but lossy” for ideation (using high-level APIs and cached aggregates), and “slow but exact” for the final dataset (direct calls to archive nodes or your own indexers). This dual-mode approach accelerates iteration while preserving rigor, and it gives you a structured way to trade latency for precision without corrupting your main results.

Step 3: Design your logical data model

Core entities and relationships

At the logical level, define a canonical schema that represents how you think about the chain. At minimum, you will have blocks, transactions, accounts, contracts and logs/events, and possibly traces for internal calls. Model explicit relationships: which transaction belongs to which block, which log belongs to which transaction, which contract was created by which account. Think in terms of primary keys and foreign keys, even if you eventually store data in a columnar warehouse or a graph database. This step is where you encode domain assumptions: for example, whether you treat contract self-destruction as the end of an entity’s lifecycle or just a state transition, and how you represent reorged blocks and uncle blocks in your tables.

Schema versioning and reproducibility

Blockchain protocols evolve: opcodes are deprecated, gas semantics change, new event types appear. If your schema is hard-coded into scripts without explicit versioning, comparisons across time become suspect. Introduce schema versions from the beginning. Maintain a small metadata registry that documents, for each dataset version, the precise extraction logic, RPC methods used, node client versions and any protocol assumptions. This is tedious but crucial for replicable research. A simple, unconventional pattern is to store your data model and transformations as code in a public repository, and treat each major change as a tagged release, similar to how software engineers manage APIs. This tightens the feedback loop between your code and your empirical claims.

Step 4: Choose physical storage and indexing strategies

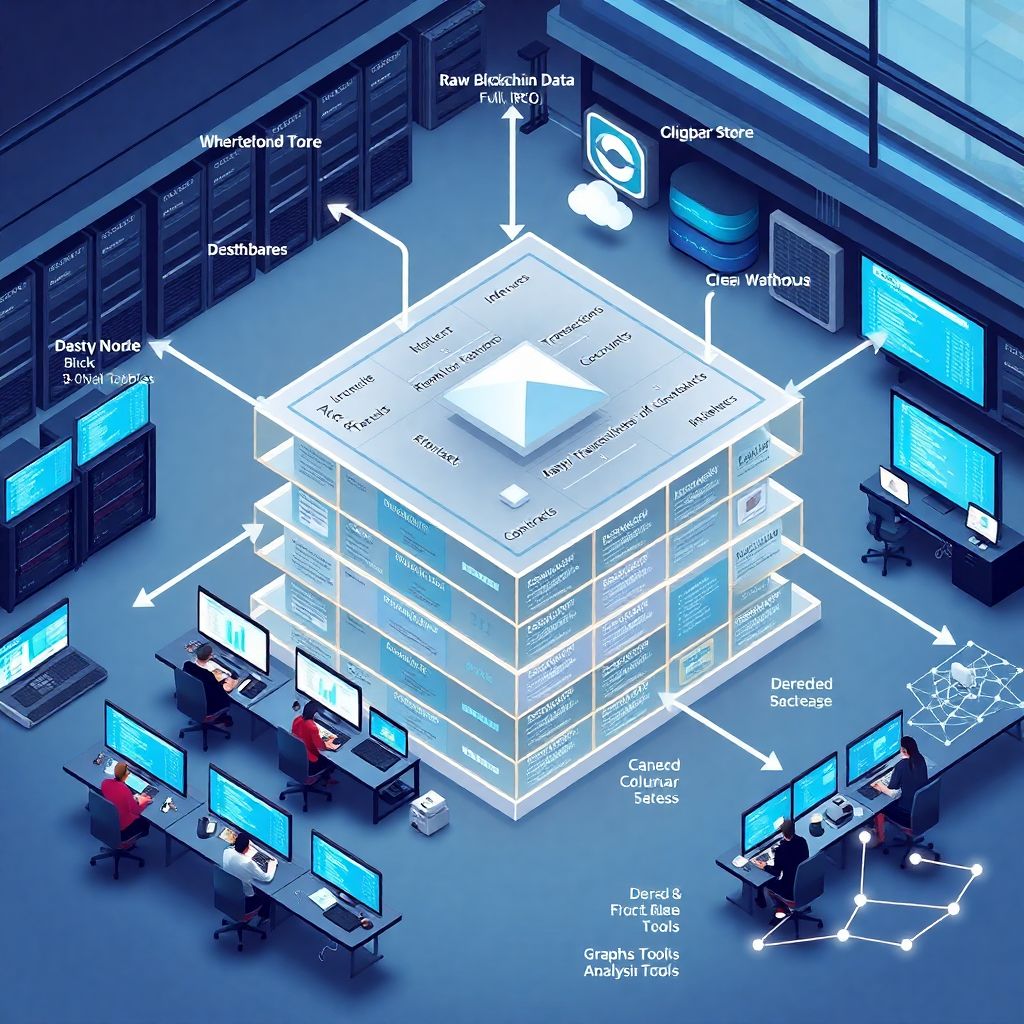

Warehouses, lakes and hybrid stores

On the physical side, decide where your curated data will live. For heavy analytical workloads, columnar warehouses like BigQuery, Snowflake or ClickHouse are natural choices, but they are not the only option. Many research teams mix an object store for raw dumps, a relational system for core reference tables, and a graph database for address-level connectivity analysis. This hybrid layout might seem overengineered, yet it maps cleanly to typical research queries: solid transactional tables for statistical models, plus graph-optimized stores for network structure. When you later integrate with blockchain data warehouse and analytics services, your internal schema clarity will make external tooling much easier to adopt or replace.

Indexing beyond the obvious

Researchers usually start by indexing on block number, transaction hash and address, which is a solid baseline but often insufficient. Consider indexing by contract method identifiers, event signatures, or even by semantic labels you derive (e.g. “DEX trade”, “bridge transfer”, “MEV bundle”). Building these higher-level indexes is an unconventional but highly effective way to cut query times and simplify complex filters. A practical approach is to maintain a derived “fact table” per major research topic, where you store only the fields necessary for your models, with pre-joined relationships from the raw layer. This star-schema-like approach, familiar from traditional analytics, is surprisingly underused in academic blockchain work yet dramatically improves performance and clarity.

Step 5: Build an extraction and transformation pipeline

Streaming vs batch ingestion

Your ingestion strategy should reflect whether you analyze static history, real-time behavior, or both. For historical research, batch extraction of blocks and transactions in fixed ranges is more stable and easier to audit. For live behavior, streaming consumption through websockets or pub/sub channels lets you handle new blocks as they arrive. Many beginners try to implement real-time ingestion prematurely and end up with inconsistent partial histories. A safer pattern is to first build a robust batch pipeline from genesis to the latest finalized block, then add a thin streaming layer that appends fresh data while periodic reconciliation jobs repair any shortfalls due to reorgs or connectivity issues.

Transformations, normalization and derived metrics

Once raw data lands, you apply transformations: decoding ABI logs, normalizing token decimals, computing derived fields such as effective gas price or slippage. Treat these steps as deterministic functions, not ad-hoc scripts. For each transformation, define inputs, outputs and assumptions in a way that another researcher could reimplement from your description. A surprisingly effective yet unconventional tactic is to generate synthetic micro-datasets that exercise each transformation on edge cases—reverted transactions, self-destructs, proxy contracts—so you can unit-test your pipeline similar to application code. This reduces the risk of quiet misparsing, which is more dangerous than visible failures because it silently corrupts analytical results.

Step 6: Select analysis tools for different research workflows

Tooling landscape for researchers

Once you have a clean dataset, you still need appropriate tools to interrogate it. Traditional stacks—Python with pandas, R, SQL—remain effective, but they must be adapted to the scale and shape of blockchain data. When comparing blockchain data analysis tools for researchers, pay attention to how they handle long time series, high-cardinality categorical variables like addresses, and nested structures inherent in traces. In many cases, pushing heavy joins and aggregations down into the warehouse or a specialized engine, then using Python or R only for modeling, yields a more reliable and reproducible workflow than pulling everything into local memory where environment differences and notebook state can skew results.

Unconventional but practical combinations

Unusual combinations can unlock new insight. For example, pair a graph database for address and contract relationships with a columnar store for transactional facts, orchestrated by a query layer that can fan out requests to each engine. Or use a lightweight in-memory OLAP engine only for exploratory slicing, while your canonical dataset remains immutable in cloud storage. Another creative approach is to embed your analytical environment directly into a containerized image that includes your exact versions of libraries and command-line tools, so reviewers or collaborators can reproduce not just your data but your runtime environment. This is particularly valuable when your work builds on enterprise blockchain data management solutions that may change features or defaults over time.

Step 7: Decide when to build vs. buy

Leveraging external services strategically

Not every team needs to maintain full nodes, custom indexers and bespoke ETL. For many projects, especially under time constraints, it is efficient to rely on third-party providers that already expose well-structured tables. Some vendors offer turnkey blockchain data warehouse and analytics services, while others specialize in labeled datasets for NFTs, DeFi, or compliance. The trick is to treat these services as components in your architecture, not as black boxes. Document exactly which provider, which schema, and which snapshot date you used, so future you—or your reviewers—can reason about potential biases, missing chains, or policy changes that might affect longitudinal comparisons or cross-platform generalizability.

When to seek expert guidance

If you plan a multi-year research agenda, it can be rational to invest in early-stage blockchain data architecture consulting instead of improvising and later rewriting the entire stack. Consultants or internal data engineers can help you design schemas and pipelines that are vendor-agnostic, so you can switch providers without invalidating past work. This is particularly useful when your institution must comply with data governance or privacy rules. Even if you ultimately build most of the pipeline yourself, a focused design review can uncover subtle issues, such as incorrectly handling chain reorganizations, misinterpreting gas usage fields, or storing timestamps without explicit time zone annotations.

Step 8: Governance, documentation and collaboration

Data catalogs, lineage and access policies

As soon as more than one person touches the data, governance matters. A lightweight data catalog that lists datasets, columns, units and known caveats can prevent repeated misunderstandings and duplicated efforts. Track lineage from raw blocks through each transformation to curated tables, so you can answer “where did this feature come from?” without archaeology. Implement access controls, even if only to protect against accidental modification of canonical tables. For teams embedded in large institutions, aligning with internal governance frameworks is often easier if you can present your stack as a specialized instance of familiar enterprise blockchain data management solutions, with clear roles, audit trails and lifecycle policies.

Documentation as a first-class research artifact

Think of your data documentation as part of the paper, not as a side note. Clearly describe your node configuration, data extraction intervals, missing-data handling and any heuristics used to classify addresses or transactions. An unconventional but useful practice is to maintain “data design memos” where you log architectural decisions and rejected approaches, such as why you abandoned one indexer in favor of another. These memos later become gold when writing limitations sections or answering reviewer questions. They also serve as a reality check for future you: if a planned shortcut seemed risky in the memo, that is a signal to treat results derived from it with caution or rerun them under a more robust pipeline.

Step 9: A concrete, step-by-step blueprint

Minimal but robust workflow outline

To make the discussion operational, here is a compact, sequential blueprint that a small research team can adopt and then extend. It is intentionally minimal, but each step is framed so that you can scale it or swap components as your questions and resources evolve. Use it as a baseline reference rather than a rigid prescription, and adapt the specifics—tools, languages, clouds—to your institutional constraints and personal preferences, provided you preserve the architectural separation between raw data, curated datasets and analysis layers.

- Start by writing a one-page data requirement spec tied to your research questions: list required chains, time spans, entities, and metrics, and explicitly mark what you will not cover.

- Select an access strategy: one stable RPC provider plus, if possible, your own archival node for final extraction; document client versions and connection parameters.

- Define a logical schema for blocks, transactions, logs and traces, including primary keys and relationships; store this schema as code and version it.

- Implement a batch ETL pipeline that ingests raw JSON from the chain, normalizes it and loads it into a structured warehouse or database with reproducible, idempotent jobs.

- Build a small set of derived tables for your key use cases, then wrap them with analysis notebooks or scripts that can be executed end-to-end from raw to final figures.

Step 10: Thinking creatively about future directions

Cross-chain, privacy-aware and experimental architectures

Looking forward, blockchain data architectures for research will increasingly involve multi-chain and privacy-preserving components. Cross-chain bridges, rollups and modular stacks mean you can no longer treat a single canonical chain as the sole source of truth. Architectures that incorporate probabilistic matching of addresses, anomaly-detection layers and differential privacy for sensitive analyses will gain relevance. An innovative approach is to build a modular internal “research bus” that consumes standardized events from several chains and rollups, decoupling your analytical logic from any single consensus layer. Another creative direction is to prototype your pipeline using a hosted blockchain data analytics platform early on, then incrementally replace external components with local equivalents as you narrow your questions and need deeper control.

Final advice for newcomers

For newcomers, the main trap is underestimating engineering and overestimating ready-made magic. Off-the-shelf blockchain data analysis tools for researchers can drastically shorten the path to first results, but they do not free you from understanding what a block, transaction, log and trace actually represent at the protocol level. The most resilient strategies usually blend pragmatic reuse of existing services with a disciplined, transparent internal architecture. If you keep your schemas explicit, your transformations deterministic, and your environment reproducible, you will be able to revisit old questions, compare chains and extend your work without starting from zero each time—even as tooling, services and protocols continue to evolve.